Scala in Action-Functional Programming in Scala

更新日期:

类型参数化

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | sealed abstract class Maybe[+A] { def isEmpty: Boolean def get: A } final case class Just[A](value: A) extends Maybe[A] { def isEmpty = false def get = value } case object Nil extends Maybe[Nothing] { def isEmpty = true def get = throw new NoSuchElementException("Nil.get") } |

协变

When using type parameters for classes or traits, you can use a + sign along with the type parameter to make it covariant (like the Maybe class in the previous example).

Covariance allows subclasses to override and use narrower types(Like Nothing) than their superclass in covariant positions such as the return value.

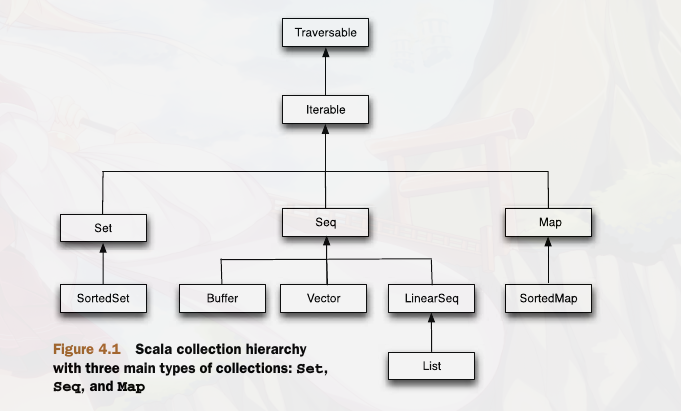

Traversable is the parent trait for all the collection types in Scala.

逆变

In the case of covariance, subtyping can go downward, as you saw in the example of List, but in contravariance it’s the opposite: subtypes go upward.

Contravariance comes in handy when you have a mutable data structure.

1 2 3 | // java 会在运行时报错 Object[] arr = new int[1]; arr[0] = "Hello, there!"; |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | // Scala uses the minus sign (-) to denote contravariance // and the plus sign (+) for covariance. // 参数是协变的, 返回值是逆变的 trait Function1[-P, +R] { ... } val addOne: Function1[Any, Int] = { x: Int => x + 1 } // 此句非法, 因为 any 为所有的对象的父类 val asString: Int => Int = { x: Int => (x.toString: Any) } |

不变

A type parameter is invariant when it’s neither covariant nor contravariant. All Scala mutable collection classes are invariant.

如 final class ListBuffer[A], 在scala中定义

1 2 3 4 5 | scala> val mxs: ListBuffer[String] = ListBuffer("pants") mxs: scala.collection.mutable.ListBuffer[String] = ListBuffer(pants) scala> val everything: ListBuffer[Any] = mxs 发生错误, 因为类型是 invariant |

类型的边界

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | sealed abstract class Maybe[+A] { def isEmpty: Boolean def get: A // 这里报错 /// Because A is a covariant type, // Scala doesn’t allow the covariant type as an input parameter. def getOrElse(default: A): A = { if(isEmpty) default else get } } |

You could solve this problem in two ways: make the Maybe class an invariant and lose all the subtyping with Just and Nil, or use type bound.

Scala provides two types of type bound: lower and upper.

An upper type bound T <: A declares that type variable T is a subtype of a type A, and A is the upper bound.

1 2 3 | def defaultToNull[A <: Maybe[_]](p: A) = {

p.getOrElse(null)

}

|

A lower bound sets the lower limit of the type parameter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | sealed abstract class Maybe[+A] {

def isEmpty: Boolean

def get: A

def getOrElse[B >: A](default: B): B = {

if(isEmpty) default else get

}

}

|

头等函数

A function is called higher order if it takes a function as an argument or returns a function as a result.

1 2 3 4 | class List[+A] ...

{

def map[B](f: A => B) : List[B]

}

|

Call-by-value, call-by-reference, and call-by-name method invocation

Java supports two types of method invocation: call-by-reference and call-by-value.

Scala also provides additional method invocation mechanisms called call-by-name and call-by-need.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | def log(m: String) = if(logEnabled) println(m) // 在这里, popErrorMessage, 总会先被运算 def popErrorMessage = { popMessageFromASlowQueue() } log("The error message is " + popErrorMessage). // 但是这样呢? 这是按需 def log(m: => String) = if(logEnabled) println(m) |

When passing an existing function (not a function object) as a parameter, Scala creates a new anonymous function object with an apply method, which invokes the original function. This is called eta-expansion.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | object ++ extends Function1[Int, Int]{ def apply(p: Int): Int = p + 1 } val ++ = (x: Int) => x + 1 object ++ extends (Int => Int) { def apply(p: Int): Int = p + 1 } val addOne: Int => Int = x => x + 1 val addTwo: Int => Int = x => x + 2 val addThree = addOne compose addTwo // like this val addThree: Int => Int = x => addOne(addTwo(x)) |

Scala collection hierarchy

In Scala you can define a traversable object as finite or infinite;

hasDefiniteSize determines whether a collection is finite or infinite.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | import java.util.{Collection => JCollection, ArrayList }

class JavaToTraversable[E](javaCollection: JCollection[E]) extends

Traversable[E] {

def foreach[U](f : E => U): Unit = {

val iterator = javaCollection.iterator

while(iterator.hasNext) {

f(iterator.next)

}

}

}

|

Overall, Vector has better performance characteristics compared to other collection types.

Buffers are always mutable, and most of the collections

I talk about here are internally built using

Buffers. The two common subclasses of Buffers are mutable.ListBuffer and

mutable.ArrayBuffer.

Unlike other collections, a Tuple is a heterogeneous collection where you can store various types of elements.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | case class Artist(name: String, genre: String) val artists = List( Artist("Pink Floyd", "Rock"), Artist("Led Zeppelin", "Rock"), Artist("Michael Jackson", "Pop"), Artist("Above & Beyond", "trance") ) for(Artist(name, genre) <- artists; if(genre == "Rock")) yield name // 会被翻译为 artists withFilter { case Artist(name, genre) => genre == "Rock" } map { case Artist(name, genre) => name } // 不用 filter 的原因, 这样会返回全部, 但是你只想返回头一个 val y = list filter { case i => go } map { case i => { go = false i } } for { ArtistWithAlbums(artist, albums) <- artistsWithAlbums album <- albums if(artist.genre == "Rock") } yield album // 被翻译为 artistsWithAlbums flatMap { case ArtistWithAlbums(artist, albums) => albums withFilter { album => artist.genre == "Rock" } map { case album => album } } |

scala.Either represents one of the two possible meaningful results, unlike Option, which returns a single meaningful result or Nothing. Either provides two subc

lazy collections

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | // view 是懒计算 List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5).view.map(_ + 1).head import scala.io._ import scala.xml.XML def tweets(handle: String) = { println("processing tweets for " + handle) val source = Source.fromURL(new java.net.URL("http://search.twitter.com/search.atom?q=" + handle)) val iterator = source.getLines() val builder = new StringBuilder for(line <- iterator) builder.append(line) XML.loadString(builder.toString) } val allTweets = Map( "nraychaudhuri" -> tweets _, "ManningBooks" -> tweets _, "bubbl_scala" -> tweets _ ) // 可以这样使用 allTweets.view.map{ t => t._2(t._1)}.head // Note that starting with Scala 2.8, for-comprehensions are now nonstrict for standard operations. // nostrict means lazy collections? for(t <- allTweets; if(t._1 == "ManningBooks")) t._2(t._1) |

Stream

The class Stream implements lazy lists in Scala where elements are evaluated only when they’re needed. If you want, you can build an infinite list in Scala using Stream , and it will consume memory based on your use.

1 2 3 4 | scala> List("zero", "one", "two", "three", "four","five").zip(Stream.from(0)) res88: List[(java.lang.String, Int)] = List((zero,0), (one,1), (two,2), (three,3), (four,4), (five,5)) |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | // 斐波那契数列, 这样做没有效率 def fib(n: Int): Int = n match { case 0 => 0 case 1 => 1 case n => fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2) } val fib: Stream[Int] = Stream.cons(0, Stream.cons(1, fib.zip(fib.tail).map(t => t._1 + t._2))) |

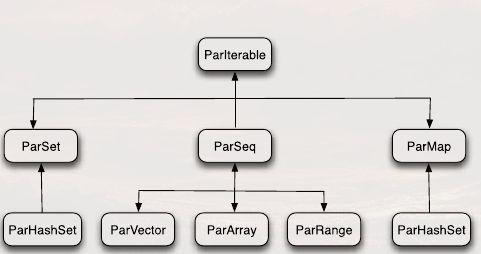

parallel collections

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | scala> import scala.collection.parallel.immutable._ import scala.collection.parallel.immutable._ scala> ParVector(10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90).map {x => println(Thread.currentThread.getName); x / 2 } // In this case tasksupport is changed to ForkJoinTask with four working threads. import scala.collection.parallel._ val pv = immutable.ParVector(1, 2, 3) pv.tasksupport = new ForkJoinTaskSupport(new scala.concurrent.forkjoin.ForkJoinPool(4)) |

1 2 3 4 | val vs = Vector.range(1, 100000) vs.par.filter(_ % 2 == 0) Vector.range(1, 100000).par.filter(_ % 2 == 0).seq |

Operations like `map, flatMap , filter , and forall are good examples of methods that would be easily parallelized.

If it takes less time to perform the operation than to create a parallel collection, then using the parallel version will reduce your perfor- mance. It also depends on the type of collection you’re using. Converting Seq to ParSeq is much faster than converting List to Vector because there’s no parallel List implementation, so when you invoke par on List you get Vector back.

函数式编程

A function provides the predictability that for a given input you will always get the same output.

But what about the functions that depend on some external state and don’t return the same result all the time? They’re functions but they’re not pure functions. A pure function doesn’t have side effects.

The value is referential transparency. Referential transparency is a property whereby an expression could be replaced by its value without affecting the program.

val v = add(10, 10) + add(5, 5)

Because add is a pure function, I can replace the function call add(10, 10) with its

result, which is 20, without changing the behavior of the program. And similarly I

could replace add(5, 5) with 10 without affecting the behavior of the program.

methods in Scala don’t have any type; type is only associated with the enclosing class, whereas functions are represented by a type and object.

pure functional program

If you can start thinking about your program as a collection of subexpressions combined into one single referentially transparent expression, you have achieved a purely functional program.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | object PureFunctionalProgram { def main(args: Array[String]):Unit = singleExpression(args.toList) def singleExpression: List[String] => (List[Int], List[Int]) = { a => a map (_.toInt) partition (_ < 30) } } // In this new solution, every time the side property is modified, //a new copy of PureSquare is returned class PureSquare(val side: Int) { def newSide(s: Int): PureSquare = new PureSquare(s) def area = side * side } |

DEMO: HTTP server

To demonstrate how this works, you’re going to build a simple HTTP server that only serves files from a directory in which the server is started. You’re going to implement the HTTP GET command. Like any server, this HTTP server is full of side effects, like writing to a socket, reading files from the filesystem, and so on. Here are your design goals for the server you’re building:

- Separate the code into different layers, pure code from the side-effecting code.

- Respond with the contents of a file for a given HTTP GET request.

- Respond with a 404 message when the file requested is missing.

Separating pure and side-effecting (impure) code. The side-effecting code should form a thin layer around the application.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | object Pure { trait Resource { def exists: Boolean def contents: List[String] def contentLength: Int } type ResourceLocator = String => Resource type Request = Iterator[Char] type Response = List[String] def get(req: Request)(implicit locator: ResourceLocator): Response = { val requestedResource = req.takeWhile(x => x != '\n') .mkString.split(" ")(1).drop(1) (_200 orElse _404)(locator(requestedResource)) } private def _200: PartialFunction[Resource, Response] = { case resource if(resource.exists) => "HTTP/1.1 200 OK" :: ("Date " + new java.util.Date) :: "Content-Type: text/html" :: ("Content-Length: " + resource.contentLength) :: System.getProperty("line.separator") :: resource.contents } private def _404: PartialFunction[Resource, Response] = { case _ => List("HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found") } } // 封装的有副作用的操作 import Pure._ case class IOResource(name: String) extends Resource { def exists = new File(name).exists def contents = Source.fromFile(name).getLines.toList def contentLength = Source.fromFile(name).count(x => true) } implicit val ioResourceLocator: ResourceLocator = name => IOResource(name) |

方法和函数

One downside of using methods is that it’s easy to depend on the state defined by the enclosing class without explicitly passing the dependencies as parameters be careful about that because that will take you away from having pure methods.

Scala infuses functional programming with OOP by transforming functions into objects.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | // 这是方法 class UseResource { // Here use is a method defined in the class UseResource. def use(r: Resource): Boolean = {...} } // 这是函数 val succ = (x: Int) => x + 1 // 也可以这样定义 val succFunction = new Function1[Int, Int] { def apply(x:Int) : Int = x + 1 } // Functions in Scala are represented by a type and object, // but methods aren’t. Methods are only associated with the enclosing class. // 可以这样改写???? val use_func: Resource => Boolean = (new UseResource).use _ |

头等函数的应用

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 | val r: Resource = getResource()

try {

useResourceToDoUsefulStuff(r)

} finally {

r.dispose()

}

def use[A, B <: Resource ](r: Resource)(f: Resource => A): A = {

try {

f(r)

} finally {

r.dispose()

}

}

// 面向对象的过程式的写法

val x = Person(firstName, lastName)

x.setInfo(someInfo)

println("log: new person is created")

mailer.mail("new person joined " + x)

x.firstName

// 提供一种函数式的解决思路

def tap[A](a: A)(sideEffect: A => Unit): A = {

sideEffect(a)

a

}

val x = Person(firstName, lastName)

tap(x) { p =>

import p._

setInfo(someInfo)

println("log: new person is created")

mailer.mail("new person joined " + x)

}.firstName

// 用上 implicity, 可以这样

object Combinators {

implicit def kestrel[A](a: A) = new {

def tap(sideEffect: A => Unit): A = {

sideEffect(a)

a

}

}

}

Person("Nilanjan", "Raychaudhuri").tap(p => {

println("First name " + p.firstName)

Mailer("some address")

}).lastName

|

柯里化函数

Function currying is a technique for transforming a function that takes multiple parameters into a function that takes a single parameter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | def taxIt(s: TaxStrategy, product: String) = { s.taxIt(product) } val taxItF = taxIt _ // 等同于 taxItF.curried // 可以这样直接定义柯里化的函数 def taxIt(s: TaxStrategy)(product: String) = { s.taxIt(product) } |

偏函数

A partial function is a function that’s only defined for a subset of input values.

In Scala partial functions are defined by trait PartialFunction[-A, +B] and extend scala.Function1 trait.

PartialFunction declares the apply method and an additional method called def isDefinedAt(a: A):Boolean. This isDefinedAt method determines whether the given partial function is defined for a given parameter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | // 定义一个偏函数 def intToChar: PartialFunction[Int, Char] = { case 1 => 'a' case 3 => 'c' } // scala 会这样翻译 new PartialFunction[Int, Char] { def apply(i: Int) = i match { case 1 => 'a' case 3 => 'c' } def isDefinedAt(i: Int): Boolean = i match { case 1 => true case 3 => true case _ => false } } |

The PartialFunction trait provides two interesting combinatory methods called orElse and andThen.

The orElse method lets you combine this partial function with another partial function. It’s much like if-else.

The andThen lets you compose transformation functions with a partial function that works on the result produced by the partial function.

递归

Recursion is where a function calls itself. One of the main benefits of recursion is that it lets you create solutions without mutation.

1 2 3 4 | def sum(xs: List[Int]): Int = xs match { case Nil => 0 case x :: ys => x + sum(ys) } |

尾递归

Head recursion is the more traditional way of doing recursion, where you perform the recursive call first and then take the return value from the recursive function and calculate the result.

In tail recursion you perform your calculation first and then execute the recursive call by passing the result of the current step to the next step.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | // 如果调用过多的, 会造成 栈溢出 def length[A](xs: List[A]): Int = xs match { case Nil => 0 case x :: ys => 1 + length(ys) } // 尾递归 def length2[A](xs: List[A]): Int = { @tailrec def _length(xs: List[A], currentLength: Int): Int = xs match { case Nil => currentLength case x :: ys => _length(ys, currentLength + 1) } _length(xs, 0) } |

ADT

Algebraic data type (ADT) is a classification. A data type in general is a set of values.

Once you’ve created ADTs, you use them in functions. ADT s become much easier to deal with if they’re implemented as case classes because pattern matching works out of the box.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | // 用 case class 定义 object ADT { sealed trait Account case class CheckingAccount(accountId: String) extends Account case class SavingAccount(accountId: String, limit: Double) extends Account case class PremiumAccount(corporateId: String, accountHolder: String) extends Account } |

function compose

To compose the two functions together, Scala provides a method called andThen, available to all function types except those with zero arguments. This andThen method behaves similarly to Unix pipes—it combines two functions in sequence and creates one function.

1 | def doubleAllEven = evenFilter andThen map(double) |

The only difference between andThen and compose is that the order of evaluation for compose is right to left.

- Write pure functions that do one thing and do it well.

- Write functions that can compose with other functions.

Monad

- Monads let you compose functions that don’t compose well, such as functions that have side effects.

- Monads let you order computation within functional programming so that you can model sequences of actions.

This application needs to calculate a price for a product by following a sequence of steps:

- Find the base price of the product.

- Apply a state code-specific discount to the base price.

- Apply a product-specific discount to the result of the previous step.

- Apply tax to the result of the previous step to get the final price.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 | object PriceCalculatorWithoutMonad { import Stubs._ case class PriceState(productId: String, stateCode: String,price: Double) def findBasePrice(productId: String, stateCode: String): PriceState = { val basePrice = findTheBasePrice(productId: String) PriceState(productId, stateCode, basePrice) } def applyStateSpecificDiscount(ps: PriceState): PriceState = { val discount = findStateSpecificDiscount(ps.productId, ps.stateCode) ps.copy(price = ps.price - discount) } def applyProductSpecificDiscount(ps: PriceState): PriceState = { val discount = findProductSpecificDiscount(ps.productId) ps.copy(price = ps.price - discount) } def applyTax(ps: PriceState): PriceState = { val tax = calculateTax(ps.productId, ps.price) ps.copy(price = ps.price + tax) } def calculatePrice(productId: String, stateCode: String): Double = { val a = findBasePrice(productId, stateCode) val b = applyStateSpecificDiscount(a) val c = applyProductSpecificDiscount(b) val d = applyTax(c) d.price } } object Stubs { def findTheBasePrice(productId: String) = 10.0 def findStateSpecificDiscount(productId: String, stateCode: String) = 0.5 def findProductSpecificDiscount(productId: String) = 0.5 def calculateTax(productId: String, price: Double) = 5.0 } |

版本二, 使用 state monad

state monad 详解

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 | trait State[S, +A] { def apply(s: S): (S, A) } // 状态子(stateMonad), 状态(state) // 每一次变化, 都抽象成一个状态 // 一个状态子(StateMonad), 就是对一次状态变化的封装 object StateMonad { trait State[S, +A] { // 每一次对 状态 操作, 都会产生一个新的状态 S, 以及一个新的值 A // 如Stack, [a, b, c, d], pop操作后, 新的状态 [b, c, d], 和新的值 a // 对 状态 s 的操作函数的串联 def apply(s: S): (S, A) // 每一次map, 都是对 新的值的操作 def map[B](f: A => B): State[S, B] = state(apply(_) match { case (s, a) => (s, f(a)) }) // 每一次 flatmap 是对 状态子 的操作 def flatMap[B](f: A => State[S, B]): State[S, B] = state(apply(_) match { case (s, a) => f(a)(s) }) } object State { def state[S, A](f: S => (S, A)) = new State[S, A] { def apply(s: S) = f(s) } def init[S]: State[S, S] = state[S, S](s => (s, s)) // 产生一个对 状态操作的 状态子 def modify[S](f: S => S) = init[S] flatMap (s => state(_ => (f(s), ()))) } } |

map and flatMap are critical parts of the monad interface—without them, no function can become a monad in Scala.

The map method of the State monad helps transform the value inside the State monad. On the other hand, flatMap helps transition from one state to another.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | def findBasePrice(ps: PriceState): Double def applyStateSpecificDiscount(ps: PriceState): Double def applyProductSpecificDiscount(ps: PriceState): Double def applyTax(ps: PriceState): Double import StateMonad.State._ def modifyPriceState(f: PriceState => Double) = modify[PriceState](s => s.copy(price = f(s))) // 整个函数, 都是对 state 进行操作的不完全实现(柯里化函数) 的串联 val stateMonad = for { _ <- modifyPriceState(findBasePrice) _ <- modifyPriceState(applyStateSpecificDiscount) _ <- modifyPriceState(applyProductSpecificDiscount) _ <- modifyPriceState(applyTax) } yield () // 最后可以这样拿来用 val initialPriceState = PriceState(productId, stateCode, 0.0) val finalPriceState = stateMonad.apply(initialPriceState)._1 val finalPrice = finalPriceState.price |

翻译后是这样的

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

def calculatePrice2(productId: String, stateCode: String): Double = {

// modify 封装对当前状态操作的一个函数, 返回一个状态子

def modifyPriceState(f: PriceState => Double) =

modify[PriceState](s => s.copy(price = f(s)))

// 很像 functor 的 monad 实现

// 这里可以看出 flatmap 的意义

val stateMonad = modifyPriceState(findBasePrice) flatMap {a =>

modifyPriceState(applyStateSpecificDiscount) flatMap {b =>

modifyPriceState (applyProductSpecificDiscount) flatMap {c =>

modifyPriceState (applyTax) map {d =>() }

}

}

}

val initialPriceState = PriceState(productId, stateCode, 0.0)

val finalPriceState = stateMonad.apply(initialPriceState)._1

val finalPrice = finalPriceState.price

finalPrice

}

|

加入 log 信息

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

def calculatePriceWithLog(productId: String, stateCode: String): Double = {

def modifyPriceState f: PriceState => Double) =

modify[PriceState](s => s.copy(price = f(s)))

def logStep(f: PriceState => String) = gets(f)

// 每一步都有对 都是对 state 的一个操作的函数

val stateMonad = for {

_ <- modifyPriceState(findBasePrice)

a <- logStep(s => "Base Price " + s)

_ <- modifyPriceState(applyStateSpecificDiscount)

b <- logStep(s => "After state discount " + s)

_ <- modifyPriceState(applyProductSpecificDiscount)

c <- logStep(s => "After product discount " + s)

_ <- modifyPriceState(applyTax)

d <- logStep(s => "After tax " + s)

} yield a :: b :: c :: d :: Nil

val (finalPriceState, log) =

stateMonad.apply(PriceState(productId, stateCode, 0.0))

finalPriceState.price

}

// gets 的定义

def gets[S,A](f: S => A): State[S, A] =

init[S] flatMap (s => state(_ => (s, f(s))))

|