Play for Scala-Web services & iteratees & WebSockets

更新日期:

- 1. Accessing web services

- 1.1. Basic requests

- 1.2. Handling responses asynchronously

- 1.3. Using the cache

- 1.4. Other request methods and headers

- 1.5. Authentication mechanisms

- 2. Dealing with streams using the iteratee library

- 2.1. Processing large web services responses with an iteratee

- 2.2. Creating other iteratees and feeding them data

- 2.3. Iteratees and immutability

- 3. WebSockets: Bidirectional communication with the browser

- 4. Using body parsers to deal with HTTP request bodies

Accessing web services

In this section, we’ll look at how to use Play’s Web Service API to connect our application to remote web services.

Basic requests

Twitter exposes a REST API that allows you to search for tweets. This search API lives at http://search.twitter.com/search.json and returns a JSON data structure containing tweets.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | case class Tweet(from: String, text: String) implicit val tweetReads = ( (JsPath \ "from_user_name").read[String] ~ (JsPath \ "text").read[String])(Tweet.apply _) def tweetList() = Action { val results = 3 val query = """paperclip OR "paper clip"""" val responseFuture = WS.url("http://search.twitter.com/search.json") .withQueryString("q" -> query, "rpp" -> results.toString) .get val response = Await.result(responseFuture, 10 seconds) val tweets = (Json.parse(response.body) \ "result").as[Seq[Tweet]] Ok(views.html.twitterrest.tweetlist(tweets)) } |

Tweetlist template

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | @(tweets: Seq[Tweet])

@main("Tweets") {

<h1>Tweets</h1>

@tweets.map { tweet =>

<ul>

<li><span>@tweet.from</span>: @tweet.text</li>

</ul>

}

}

|

Handling responses asynchronously

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | val resultFuture: Future[Result] = responseFuture.map { response => val tweets = Json.parse(response.body).\("results").as[Seq[Tweet]] Ok(views.html.twitterrest.tweetlist(tweets)) } def tweetList() = Action { Async { val results = 3 val query = """paperclip OR "paper clip"""" val responseFuture = WS.url("http://search.twitter.com/search.json") .withQueryString("q" -> query, "rpp" -> results.toString).get responseFuture.map { response => val tweets = Json.parse(response.body).\("results").as[Seq[Tweet]] Ok(views.html.twitterrest.tweetlist(tweets)) } } } |

Using the cache

For all cache methods, you need an implicit play.api.Application in scope. You

can get one by importing play.api.Play.current.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | // it’ll compute Product.getBestSeller() and // cache it for 1800 seconds as well as return it val bestSellerProduct: Product = Cache.getOrElse("product-bestseller", 1800){ Product.getBestSeller() } |

Caching an entire action

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | def tweetList() = Cached("action-tweets", 120) { Action { Async { val results = 3 val query = """paperclip OR "paper clip"""" val responseFuture = WS.url("http://search.twitter.com/search.json") .withQueryString("q" -> query, "rpp" -> results.toString).get responseFuture.map { response => val tweets = Json.parse(response.body).\("results").as[Seq[Tweet]] Ok(views.html.twitterrest.tweetlist(tweets)) } } } } |

You can use this to cache a recommendations page for each user ID:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | def userIdCacheKey(prefix: String) = { (header: RequestHeader) =>

prefix + header.session.get("userId").getOrElse("anonymous")

}

def recommendations() = Cached(userIdCacheKey("recommendations-"), 120) {

Action { request =>

val recommendedProducts =

RecommendationsEngine.recommendedProductsForUser(request.session.get("userId"))

Ok(views.html.products.recommendations(recommendedProducts))

}

}

|

Other request methods and headers

As well as GET requests, you can of course use the WS library to send PUT , POST , DELETE, and HEAD requests.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | val newUser = Json.toJson(Map( "name" -> "John Doe", "email" -> "j.doe@example.com")) val responseFuture = WS.url("http://api.example.com/users").post(newUser) WS.url("http://example.com").withHeaders(HeaderNames.ACCEPT -> "application/json") |

Authentication mechanisms

OAuth requests are authenticated using a signature that’s added to each request, and this signature is calculated using secret keys that are shared between the server that offers OAuth protected resources and a third party that OAuth calls the consumer. Also, OAuth defines a standard to acquire some of the required keys and the flow that allows end users to grant access to protected resources.

The OAuthCalculator can calculate signatures given a consumer key, a consumer secret wrapped in a ConsumerKey , and an access token and token secret wrapped in a RequestToken.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | val consumerKey = ConsumerKey( "52xEY4sGbPlO1FCQRaiAg", "KpnmEeDM6XDwS59FDcAmVMQbui8mcceNASj7xFJc5WY") val accessToken = RequestToken( "16905598-cIPuAsWUI47Fk78guCRTa7QX49G0nOQdwv2SA6Rjz", "yEKoKqqOjo4gtSQ6FSsQ9tbxQqQZNq7LB5NGsbyKU") def postTweet() = Action { val message = "Hi! This is an automated tweet!" val data = Map( "status" -> Seq(message)) val responseFuture = WS.url("http://api.twitter.com/1/statuses/update.json") .sign(OAuthCalculator(consumerKey, accessToken)).post(data) Async(responseFuture.map(response => Ok(response.body))) } |

Dealing with streams using the iteratee library

Play’s iteratee library is in the play.api.libs.iteratee package.

This library is considered a cornerstone of Play’s reactive programming model.

It contains an abstraction for performing IO operations, called an iteratee.

Twitter not only offers the REST API that we saw in the previous section, but also a streaming API.

You start out using this API much like the regular API: you construct an HTTP request with some parameters that specify which tweets you want to retrieve. Twitter will then start returning tweets. But unlike the REST API, this streaming API will never stop serving the response. It’ll keep the HTTP connection open and will continue sending new tweets over it.

Processing large web services responses with an iteratee

If the web service sends the response in chunks, the WS library buffers these chunks until it has the complete HTTP response. The buffering strategy breaks down when trying to use the Twitter API.

We need another approach, where we can start using parts of the response as soon as they arrive in our application, without needing to wait for the entire response. And this is exactly what an iteratee can do. An iteratee is an object that receives each individual chunk of data and can do something with that data.

When dealing with the Twitter streaming API, we’d want to use an iteratee that converts the HTTP response chunks into tweet objects, and send them to another part of our application, perhaps to be stored in a database.

Iteratees are instances of the Iteratee class, and they can most easily be con- structed using methods on the Iteratee object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | // The foreach[A] method on the Iteratee object takes a single parameter, a function // that takes a chunk of type A and returns an Iteratee[A, Unit] // For each chunk that’s received, a string is constructed and printed. // The first indicates the Scala type for the chunks that the iteratee accepts. val loggingIteratee = Iteratee.foreach[Array[Byte]] { chunk => val chunkString = new String(chunk, "UTF-8") println(chunkString) } WS.url("https://stream.twitter.com/1/statuses/sample.json") .sign(OAuthCalculator(consumerKey, accessToken)) .get(_ => loggingIteratee) |

Creating other iteratees and feeding them data

The Iteratee object exposes more methods that we can use to create iteratees.

1 2 3 4 | // accepts Int chunks, and sums these chunks. val summingIteratee = Iteratee.fold(0){ (sum: Int, chunk: Int) => sum + chunk } |

It turns out that the Iteratee class has a counterpart: Enumerator . An enumerator is a producer of chunks.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | val intEnumerator = Enumerator(1,6,3,7,3,1,1,9) // it’ll return a future of a new iteratee val newIterateeFuture: Future[Iteratee[Int, Int]] = intEnumerator(summingIteratee) // With a regular map , we’d get a Future[Future[Int]], but with flatMap, we get a Future[Int] val resultFuture: Future[Int] = newIterateeFuture.flatMap(_.run) resultFuture.onComplete(sum => println("The sum is %d" format sum)) |

Iteratees and immutability

As mentioned before, the iteratee library is designed to be immutable: operations don’t change the iteratee that you perform it on, but they return a new iteratee.

You can apply it to different enumerators as often as you like without problems.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | // here are both an immutable and a mutable iteratee that do the same thing: sum integers:

val immutableSumIteratee = Iteratee.fold(0){ (sum: Int, chunk: Int) =>

sum + chunk

}

val mutableSumIteratee = {

var sum = 0

Iteratee.foreach[Int](sum += _).mapDone(_ => sum)

}

|

WebSockets: Bidirectional communication with the browser

The most basic approach is polling: the browser sends a request to the server to ask for new data every second or so.

When polling, the browser sends a request to the server at a regular interval requesting new messages. Often, the server will have nothing.

A more advanced workaround is Comet, which is a technique to allow the server to push data to a client. With Comet, the browser starts a request and the server keeps the connection open until it has something to send.

A real-time status page using WebSockets

From the application’s perspective, a WebSocket connection is essentially two independent streams of data: one stream of data incoming from the client and a second stream of data to be sent to the client.

To handle the incoming stream of data, you need to provide an iteratee. You also provide an enumerator that’s used to send data to the client. With an iteratee and an enumerator, you can construct a WebSocket, which comes in the place of an Action.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | @(implicit request: RequestHeader)

@main("Server Status") {

<script type="text/javascript">

$(function(){

var ws = new WebSocket("@route.WebSockets.statusFeed.webSocketUrL()")

ws.onmessage = function(msg) {

$('#load-average').text(msg.data)

}

});

</script>

<h1>System load average: <span id="load-average"></span></h1>

}

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | def statusFeed() = WebSocket.using[String] { implicit request => // iterratee ignoring incoming message val in = Iteratee.ignore[String] val out = Enumerator.repeatM { Promise.timeout(getLoadAverage), 3 seconds) } (in, out) } |

1 | GET /WebSockets/statusFeed controllers.WebSockets.statusFeed() |

A simple chat application

Play allows you to make such an enumerator with Concurrent.broadcast .

This method returns a tuple with an enumerator and a Channel.

This channel is tied to the enumerator and allows you to

push chunks into the enumerator:

1 2 3 | val (enumerator, channel) = Concurrent.broadcast[String]

channel.push("Hello")

channel.push("World")

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 | case class Join(nick: String) case class Leave(nick: String) case class Broadcast(message: String) class ChatRoom extends Actor { var users = Set[String]() var (enumerator, channle) = Concurrent.broadcast[String] def receive = { case Join(nick) => { if(!users.contains(nick)) { val iteratee = Iteratee.foreach[String] { message => self ! broadcast("%s: %s" format (nick, message)) }.mapDone { _ => self ! Leave(nick) } users += nick channel.push("User %s has joined the room, now %s users" format(nick, users.size)) sender ! (iteratee, enumerator) } else { val enumerator = Enumerator("Nickname %s is already in use." format nick) val iteratee = Iteratee.ignore sender ! (iteratee, enumerator) } } case Leave(nick) => { users -= nick channel.push("User %s has left the room, %s users left" format(nick, users.size)) } case Broadcast(msg: String) => channel.push(msg) } } // Chat controller object Chat extends Controller { impplicit val timeout = Timeout(1 seconds) val room = Akka.system.actorOf(Props[ChatRoom]) def showRoom(nick: String) = Action {implicit request => Ok(views.html.chat.showRoom(nick)) } def chatSocket(nick: String) = WebSocket.async { request => val channelsFuture = room ? Join(nick) channlesFuture.mapTo[(Iteratee[String, _], Enumerator[String])] } } |

1 2 | GET /room/:nick controllers.Chat.room(nick) GET /room/socket/:nick controllers.Chat.chatSocket(nick) |

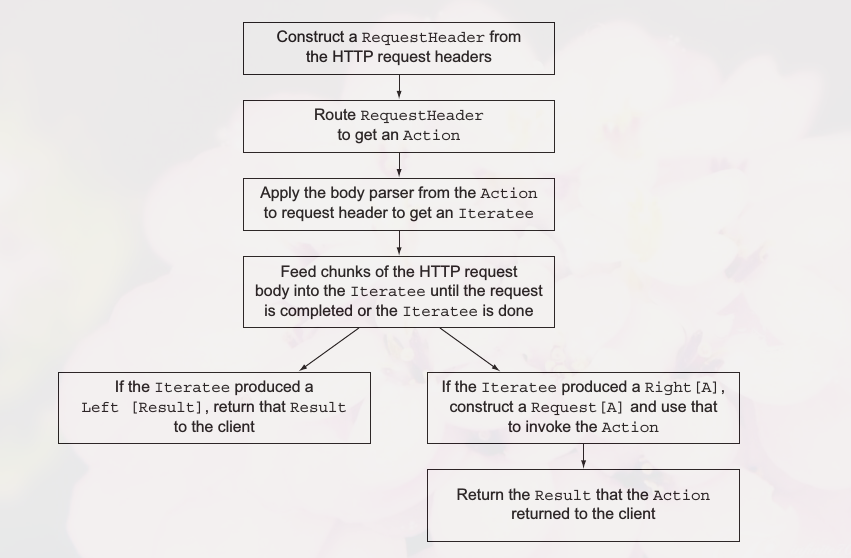

Using body parsers to deal with HTTP request bodies

HTTP requests are normally processed when they’ve been fully received by the server. An action is only invoked when the request is complete, and when the body parser is done parsing the body of the request.

In this section, we’ll show how body parsers work, how you can use and compose existing body parsers, and finally how you can build your own body parsers from scratch.

Structure of a body parser

A body parser is an object that knows what to make of an HTTP request body. A JSON body parser, for example, knows how to construct a JsValue from the body of an HTTP request that contains JSON data.

A body parser can also choose to return an error Result; for example, when the user exceeds the storage quota, or when the HTTP request body doesn’t conform to what the body parser expects, like a non-JSON body for a JSON body parser.

A BodyParser is a function with a RequestHeader parameter returning an iteratee. The iteratee consumes chunks of type Array[Byte] and eventually produces either a play.api.mvc.Result or an A, which can be anything.

An Action in Play not only defines the method that constructs a Result from a

Request[A], but it also contains the body parser that must be used for requests that

are routed to this action.

the following two Action definitions construct the same Action:

1 2 3 4 5 | Action { // block }

// The anyContent body parser is of type BodyParser[AnyContent],

// so your action will receive a Request[AnyContent]

// AnyContent is a convenient one; it has the methods asJson, asText, asXml, and so on,

Action(BodyParsers.parse.anyContent) { // block }

|

the BodyParsers.parse.json body parser will result in a Request[JsValue],

and then the body field of the Request is of type JsValue.

With the json body parser, a BadRequest response is sent back to the client

automatically when the body doesn’t contain valid JSON.

Using built-in body parsers

Play has many more body parsers, all available on the Bodyparsers.parse object.

1 2 3 4 5 | // This action will return an EntityTooLarge HTTP response // when the body is larger than 10,000 bytes. def myAction = Action(parse.json(10000)) { // foo } |

If you don’t specify a maximum length, the text, JSON, XML, and

URL-encoded body parsers default to a limit of 512 kilobytes. This can be changed in

application.conf: parsers.text.maxLength = 1m

1 2 3 4 5 6 | // To store uploaded file, you can use the temporaryFile body parser. def upload = Action(parse.temporaryFile) { request => val destinationFile = Play.getFile("uploads/myfile") request.body.moveTo(destinationFile) Ok("File successfully uploaded!") } |

Composing body parsers

The built-in body parsers are fairly basic. It’s possible to compose these basic body parsers into more complex ones that have more complex behavior if you need that.

1 2 3 4 | // Play also has a file body parser that takes a java.io.File as a parameter: def store(filename: String) = Action(parse.file(Play.getFile(filename))) { request => Ok("Your file is saved!") } |

Suppose we want to make a body parser that works like the file body parser, but only saves the file if the content type is some given value.

We can use the BodyParsers.parse.when method to construct a

new body parser from a predicate, an existing body parser,

and a function constructing a failure result:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | def fileWithContentType(filname:String, contentType: String) = parse.when( requestHeader => requestHeader.contentType == contentType, parse.file(Play.getFile(filename)), requestHeader => BadRequest( // Existing body parser "Expected a '%s' content type, but found %s". format(contentType, requestHeader.contentType))) // We can use this body parser as follows: def savePdf(filename: String) = Action(fileWithContentType(filename, "application/pdf")) { request => Ok("Your file is saved!") } |

We can start with the temporaryFile body parser to store the file on disk and then upload it to MongoDB.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | def mongoDbStorageBodyParser(dbName: String) = parse.temporaryFile.map { temporaryFile => // Here some code to store the file in MongoDB // and get an objectId objectId } val dbName = Play.configuration.getString("mongoDbName").getOrElse("mydb") def saveInMongo = Action(mongoDbStorageBodyParser(dbName)) { request => Ok("Your file was saved with id %s" format request.body) } |

Building a new body parser

In this section, we’ll build another body parser that allows a user to upload a file. This time, though, it won’t be stored on disk or in MongoDB, but on Amazon’s Simple Storage Service, better known as S3.

The underlying library that Play uses, Async HTTP Client (AHC), does support pushing chunks of data into a request body

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 | private lazy val client = {

val playConfig = WS.client.getConfig

new AsyncHttpClient(new GrizzlyAsyncHttpProvider(playConfig), playConfig)

}

// Amazon requires requests to be signed.

def sign(method: String, path: String,

secretKey: String,

date: String,

contentType: Option[String] = None,

aclHeader: Option[String] = None) = {

val message = List(method, "",

contentType.getOrElse(""),

date, aclHeader.map("x-amz-acl:" + _).getOrElse(""), path).mkString("\n")

// Play’s Crypto.sign method returns a Hex string,

// instead of Base64, so we do hashing ourselves.

val mac = Mac.getInstance("HmacSHA1")

mac.init(new SecretKeySpec(secretKey.getBytes("UTF-8"), "HmacSHA1"))

val codec = new Base64()

new String(codec.encode(mac.doFinal(message.getBytes("UTF-8"))))

}

def buildRequest(bucket: String, objectId: String, key: String,

secret: String, requestHeader: RequestHeader): (Request, FeedableBodyGenerator) = {

val expires = dateFormat.format(new Date())

val path = "/%s/%s" format (bucket, objectId)

val acl = "public-read"

val contentType = requestHeader.headers.get(HeaderNames.CONTENT_TYPE)

.getOrElse("binary/octet-stream")

val auth = "AWS %s:%s" format (key, sign("PUT", path, secret,

expires, Some(contentType), Some(acl)))

val url = "https://%s.s3.amazonaws.com/%s" format (bucket, objectId)

val bodyGenerator = new FeedableBodyGenerator()

val request = new RequestBuilder("PUT")

.setUrl(url)

.setHeader("Date", expires)

.setHeader("x-amz-acl", acl)

.setHeader("Content-Type", contentType)

.setHeader("Authorization", auth)

.setContentLength(requestHeader.headers

.get(HeaderNames.CONTENT_LENGTH).get.toInt)

.setBody(bodyGenerator)

.build()

(request, bodyGenerator)

}

|

Amazon S3 body parser

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | def S3Upload(bucket: String, objectId: String) = BodyParser { requestHeader => val awsSecret = Play.configuration.getString("aws.secret").get val awsKey = Play.configuration.getString("aws.key").get val (request, bodyGenerator) = buildRequest(bucket, objectId, awsKey, awsSecret, requestHeader) S3Writer(objectId, request, bodyGenerator) } def S3Writer(objectId: String, request: Request, bodyGenerator: FeedableBodyGenerator):Iteratee[Array[Byte], Either[Result, String]] = { // We execute the request, but we can send body chunks afterwards. val responseFuture = client.executeRequest(request) Iteratee.fold[Array[Byte], FeedableBodyGenerator](bodyGenerator) { (generator, bytes) => val isLast = false generator.feed(new ByteBufferWrapper(ByteBuffer.wrap(bytes)), isLast) generator } mapDone { generator => val isLast = true val emptyBuffer = new ByteBufferWrapper(ByteBuffer.wrap(Array[Byte]())) generator.feed(emptyBuffer, isLast) val response = responseFuture.get response.getStatusCode match { case 200 => Right(objectId) case _ => Left(Forbidden(response.getResponseBody)) } } } |

Enumeratees can sit between enumerators and iteratees and modify the stream. Elements of the stream can be removed, changed, or grouped.